Australia May Soon Address Misinformation and Disinformation

EC proposes new cyber standards for EU institutions; U.S. finds spike in cyber crime

The Wavelength is moving! This week, you’ll get the same great content, but from the Ghost platform from this email address. The move will allow for a price decrease because of reduced costs.

And, it bears mention that content on technology policy, politics, and law that preceded the Wavelength can be found on my blog.

Photo by Cody Board on Unsplash

A report issued this week presages Australia tightening regulation of social media platforms with respect to misinformation and disinformation. At present, a government fostered code of conduct for large digital platforms that is voluntary governs misinformation and disinformation. The report has found problems with the industry developed and operated code and is asking the government for more power to regulate digital platforms on a modest scale that would put more muscle into the current framework.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) released its report “A report to government on the adequacy of digital platforms’ disinformation and news quality measures” as part of its duties in the government’s larger ongoing examination of digital markets. In conjunction with the report, Minister for Communications, Urban Infrastructure, Cities and the Arts Paul Fletcher MP vowed that “[t]he Morrison Government will introduce legislation this year to combat harmful disinformation and misinformation online…[that] will provide the ACMA with new regulatory powers to hold big tech companies to account for harmful content on their platforms.” He added that “[t]he Government will consult on the scope of the new powers in the coming weeks ahead of introducing legislation into the Parliament in the second half of 2022.”

Of course, this is not Australia’s first time at the online harms rodeo with the recently enacted “Online Safety Bill 2021” and the “Online Safety (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2021” taking effect in January 2022 (see here and here). However, those bills address cyber-abuse and cyber-bullying while the ACMA report covers the harm of misinformation and disinformation. Moreover, it appears based on the ACMA’s recommendations, the government will not propose anything so far reaching as the other bills.

Naturally, Australia is not the only nation concerned about disinformation and misinformation. The European Union (EU) is considering legislation, the Digital Services Act, that would “help to tackle harmful content (which might not be illegal) and the spread of disinformation” according to the EU Parliament (see here for more on the bill as introduced.) Under the United Kingdom’s (UK) recently released “Online Safety Bill,” the government could order some digital platforms to provide notice of how it is handling disinformation and misinformation during national emergencies, including those involving public health and national security (see here for more detail and analysis.)

Of course, whether and in what form Canberra moves forward with regulating online misinformation and disinformation will depend on the outcome of this year’s election and if Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s Liberal-National coalition is returned to power.

Moreover, one must keep in mind Facebook and Google’s responses to the Australian government’s legislation mandating compensation for using news media content. One company actually shut down services in the country, and the other threatened to pull services, with both looking to pressure Canberra through disruption of citizens’ use of the platforms. These tactics did achieve some changes, but the legislation was ultimately enacted. With the modest changes to the status quo the Morrison government seems to be proposing, U.S. tech giants may be more comfortable and see no need to resort to such tactics.

Some background would be helpful. The Australian Consumer and Competition Commission’s (ACCC) 2019 final report in its Digital Platforms Inquiry (DPI) recommended that social media platforms establish a voluntary code.[1] In its response to the ACCC, the government stated it would “ask the major digital platforms to develop a voluntary code (or codes) of conduct for disinformation and news quality” with the ACMA overseeing the process. The agency released its position paper on developing a code, and DIGI, “a not for profit industry association representing the digital industry in Australia,” produced a the Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation that was launched in February 2021. The EU has a similar code, the “Code of Practice on Disinformation,” that preceded Australia’s and that it is also seeking to improve.

Ultimately, Adobe, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Redbubble, TikTok and Twitter adopted the Australian code, which seeks to encourage signatories to implement “safeguards to protect Australians against harm from online disinformation and misinformation, and to adopting a range of scalable measures that reduce its spread and visibility.” And yet, as the ACMA recounts, the code is voluntary and if a company opts in, there are only two mandatory commitments: “reducing the risk of harms arising from disinformation and misinformation – and to publish an annual report.” There are additional duties digital platforms may sign up for in the code, but companies are not obligated to do so. For example, the code also aspires to “[d]isrupt advertising and monetisation incentives for Disinformation,” but no signatory must opt into this goal. The ACMA provided this chart:

As a way of defining the problem, the ACMA commissioned research to determine the extent and scope of disinformation and misinformation with respect to COVID-19 in Australia. The agency explained it “undertook a mixed-methods study focused on COVID-19 misinformation…[and] [k]ey insights include:

§ Most adult Australians (82%) report having experienced misinformation about COVID-19 over the past 18 months. Of these, 22% of Australians report experiencing ‘a lot’ or ‘a great deal’ of misinformation online.

§ Belief in COVID-19 falsehoods or unproven claims appears to be related to high exposure to online misinformation and a lack of trust in news outlets or authoritative sources. Younger Australians are most at risk from misinformation, however there is also evidence of susceptibility among other vulnerable groups in Australian society.

§ Australians are most likely to see misinformation on larger digital platforms, like Facebook and Twitter. However, smaller private messaging apps and alternative social media services are also increasingly used to spread misinformation or conspiracies due to their less restrictive content moderation policies.

§ Misinformation typically spreads via highly emotive and engaging posts within small online conspiracy groups. These narratives are then amplified by international influencers, local public figures, and by coverage in the media. There is also some evidence of inorganic engagement and amplification, suggesting the presence of disinformation campaigns targeting Australians.

§ Many Australians are aware of platform measures to remove or label offending content but remain sceptical of platform motives and moderation decisions. There is widespread belief that addressing misinformation requires all parties – individuals, platforms and governments – to take greater responsibility to improve the online information environment and reduce potential harms.

The ACMA assessed what works and what does not with the code. The ACMA praised the code’s outcomes based approach instead of a more means directed approach and thinks this should continue to be the approach in the future. However, the agency suggested an opt out model for the code may lead to better results if “platforms would be permitted to opt out of an outcome only where that outcome is not relevant to their services.”

The ACMA noted that “the code incorporates complex definitions and uses technical jargon that may make aspects of the code unclear to users and the general public.” The agency conceded that “[t]he development of definitions has been challenging due to the relatively novel nature of the problem and lack of consensus on definitions among industry, researchers and international organisations.” Nonetheless, the agency concluded that “clear definitions and simple language would make the code more accessible to the public and increase transparency of platform measures.”

The agency noted the code only requires platforms to remove content that presents the risk of serious and imminent harm. In fact, the code stipulates that these harms are those “which pose an imminent and serious threat to:

§ democratic political and policymaking processes such as voter fraud, voter interference, voting misinformation; or

§ public goods such as the protection of citizens' health, protection of marginalised or vulnerable groups, public safety and security or the environment.

However, the ACMA has concerns “that the effectiveness of the code will be limited by an excessively narrow definition, or interpretation, of harm.” While the agency agrees that the standard should pertain to serious harm because doing so will protect the freedom of expression to the greatest extent possible, it has concerns about the imminent component:

However, the requirement that harm must also be ‘imminent’ introduces a temporal element, which may be interpreted differently by signatories. If read narrowly, the ‘imminent’ test would likely exclude a range of chronic harms that can result from the cumulative effect of misinformation over time, such as reductions in community cohesion and a lessening of trust in public institutions. As outlined in Chapter 2, these types of chronic harms can increase vaccine hesitancy, promote disengagement from democratic processes, and result in a range of tangible, real-world harms to both individual users and society at large.

Consequently, the ACMA thinks imminent should be stricken from the definition of harm.

The ACMA also articulated its concerns about the exclusion of private messaging services, some of which are used increasingly to spread both misinformation and disinformation (e.g. WhatsApp and Telegram). The agency also wants language that would allow to the inclusion of smaller and emerging platforms, which is where some spreaders of conspiracy material are migrating as the larger platforms are cracking down in response to pressure from governments around the world.

The agency critiqued the reports the signatories have submitted, finding them varied in quality and transparency. The ACMA observed that “[o]n the whole, reporting lacked systematic data, metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs) that establish a baseline and enable the tracking of platform and industry performance against code outcomes over time.” Moreover, the agency noted “[t]he way in which signatories assess harm and apply proportionality and risk considerations under their policies is not always transparent in their reports.”

Ultimately, the ACMA stated further incentives may be needed to address this aspect of the code if the EU’s experiences with its code on disinformation are representative. The ACMA conceded that “[a]s multinational corporations, internal policies and priorities may limit the extent to which platforms are willing to invest in the necessary systems and resources to allow for more detailed, Australia-specific reporting.” As a result, the agency calls for additional incentives, which seems like a nod toward greater authority.

The ACMA noted that “the code incorporates complex definitions and uses technical jargon that may make aspects of the code unclear to users and the general public.” The agency conceded that “[t]he development of definitions has been challenging due to the relatively novel nature of the problem and lack of consensus on definitions among industry, researchers and international organisations.” Nonetheless, the agency concluded that “clear definitions and simple language would make the code more accessible to the public and increase transparency of platform measures.”

In his press statement, Minister for Communications, Urban Infrastructure, Cities and the Arts Paul Fletcher MP stated “the Government welcomed all five of the recommendations made in ACMA’s report.” The agency summarized its recommendations:

§ Recommendation 1: The government should encourage DIGI to consider the findings in this report when reviewing the code in February 2022.

§ Recommendation 2: The ACMA will continue to oversee the operation of the code and should report to government on its effectiveness no later than the end of the 2022- 23 financial year. The ACMA should also continue to undertake relevant research to inform government on the state of disinformation and misinformation in Australia.

§ Recommendation 3: To incentivise greater transparency, the ACMA should be provided with formal information-gathering powers (including powers to make record keeping rules) to oversee digital platforms, including the ability to request Australia- specific data on the effectiveness of measures to address disinformation and misinformation.

§ Recommendation 4: The government should provide the ACMA with reserve powers to register industry codes, enforce industry code compliance, and make standards relating to the activities of digital platforms’ corporations. These powers would provide a mechanism for further intervention if code administration arrangements prove inadequate, or the voluntary industry code fails.

§ Recommendation 5: In addition to existing monitoring capabilities, the government should consider establishing a Misinformation and Disinformation Action Group to support collaboration and information-sharing between digital platforms, government agencies, researchers and NGOs on issues relating to disinformation and misinformation.

Regarding possible legislation, the ACMA suggested the following:

§ The ACMA currently has no regulatory powers to underpin its oversight role. The establishment of a suite of reserve regulatory powers would allow the ACMA to take further action if required. Actions could range from buttressing the current voluntary Code with a registration process to incentivise industry to develop and enforce compliance with codes, through to standards-making powers if a code fails to address those harms. Such reserve powers would be defined by the government and may be confined to issues of most concern.

§ Developing this reserve power framework would also improve incentives for industry to improve voluntary arrangements and provide an appropriate backstop for further action if required. Care would be needed to ensure the approach is responsive to the risks of disinformation and misinformation, and the concerns of stakeholders. This can be balanced by a robust public consultation process.

Other Developments

Photo by Mariano Nocetti on Unsplash

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) issued the documents adopted its March plenary: Guidelines on Art. 60 GDPR; Guidelines on dark patterns in social media platform interfaces; EDPB-EDPS Joint Opinion on the extension of Covid-19 certificate Regulation; Toolbox on essential data protection safeguards for enforcement cooperation between EEA and third country SAs.

The United States (U.S.) Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR), Steve Daines (R-MT), Cory Booker (D-NJ), and Mike Lee (R-UT) and Representatives Ted Lieu (D-CA) and Warren Davidson (R-OH) introduced the “Government Surveillance Transparency Act” (S.3888) “to require public reporting and notice of the hundreds of thousands of criminal surveillance orders issued by courts each year, which are typically sealed, indefinitely, keeping government surveillance hidden for years, even when the targets are never charged with any crime.”

The European Commission (EC) “proposed new rules to establish common cybersecurity and information security measures across the EU institutions, bodies, offices and agencies…[that] aims to bolster their resilience and response capacities against cyber threats and incidents, as well as to ensure a resilient, secure EU public administration, amidst rising malicious cyber activities in the global landscape.”

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) warned “social media influencers who discuss financial products and services online…[about] how financial services laws apply” to them.

The United States (U.S.) Department of Justice announced its first settlement of a civil cyber-fraud case under its Civil Cyber-Fraud Initiative with “Comprehensive Health Services LLC (CHS)…agree[ing] to pay $930,000 to resolve allegations that it violated the False Claims Act by falsely representing to the State Department and the Air Force that it complied with contract requirements relating to the provision of medical services at State Department and Air Force facilities in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

The United Kingdom’s (UK) Data Minister Chris Philp “delivered a speech at AI UK on the power data and artificial intelligence have in improving innovation and driving growth.”

The United States (U.S.) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) “convened a three-hour call with over 13,000 industry stakeholders to provide an update on the potential for Russian cyberattacks against the U.S. homeland and answer questions from a range of stakeholders across the nation.”

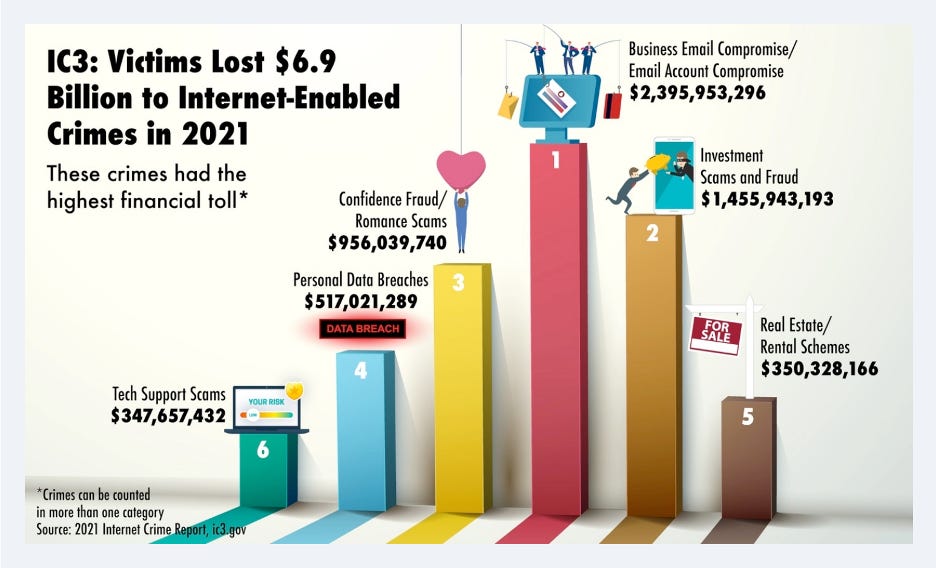

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) FBI released the “Internet Crime Complaint Center 2021 Internet Crime Report” that “includes information from 847,376 complaints of suspected internet crime—a 7% increase from 2020—and reported losses exceeding $6.9 billion.”

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has “instituted Federal Court proceedings against Facebook owner Meta Platforms, Inc. and Meta Platforms Ireland Limited (together: Meta) alleging that they engaged in false, misleading or deceptive conduct by publishing scam advertisements featuring prominent Australian public figures.”

Tweet of the Day

Further Reading

Photo by Tuqa Nabi on Unsplash

“Telegram Becomes a Digital Battlefield in Russia-Ukraine War” By Vera Bergengruen — TIME

“The online volunteers hunting for war crimes in Ukraine” By Tanya Basu — MIT Technology Review

“A Mysterious Satellite Hack Has Victims Far Beyond Ukraine” By Matt Burgess — WIRED

“Israel blocked Ukraine from buying Pegasus spyware, fearing Russia’s anger” By Stephanie Kirchgaessner — The Guardian

“DHS seeks to automate video surveillance on ‘soft targets’ like transit systems, schools” By Dave Nyczepir — Fedscoop

“Nothing’s Carl Pei Wants to Start a Smartphone Revolution (Again)” By Andrew Williams — WIRED

“The fight over anonymity is about the future of the internet” By David Pierce and Issie Lapowsky — Protocol

“How Facebook’s real-name policy changed social media forever” By Jeff Kosseff — Protocol

“Brazil Lifts Its Ban on Telegram After Two Days” By Jack Nicas and André Spigariol — New York Times

“How Kremlin accounts manipulate Twitter” By James Clayton — BBC

“Unlicensed Instagram and TikTok influencers offering financial advice could face jail time, Asic warns” By Ben Butler — The Guardian

“CIA applies lessons from Iraq 'debacle' in information battle over Russian invasion of Ukraine” By Zach Dorfman — Yahoo News

Coming Events

Photo by William Moreland on Unsplash

§ 23 March

o The United Kingdom’s House of Commons’ Science and Technology Committee will hold a formal meeting (oral evidence session) in its inquiry on “The right to privacy: digital data”

o The United States (U.S.) Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee will hold a hearing that “will examine the correlation between American competitiveness and semiconductors; the impact of vulnerabilities in our semiconductor supply chains; and the importance of CHIPS legislation within the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act (USICA) of 2021 and the America COMPETES Act of 2022.”

§ 24 March

o The United Kingdom’s (UK) House of Lords Fraud Act 2006 and Digital Fraud Committee will hold a formal meeting (oral evidence session) regarding “what measures should be taken to tackle the increase in cases of fraud.”

o The United Kingdom’s House of Commons General Committee will hold two formal meetings on the “Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure Bill” “A Bill to make provision about the security of internet-connectable products and products capable of connecting to such products; to make provision about electronic communications infrastructure; and for connected purposes.”

§ 29-30 March

o The California Privacy Protection Agency Board will be holding “public informational sessions.”

§ 31 March

o The United Kingdom’s (UK) House of Lords Fraud Act 2006 and Digital Fraud Committee will hold a formal meeting (oral evidence session) regarding “what measures should be taken to tackle the increase in cases of fraud.”

§ 6 April

o The European Data Protection Board will hold a plenary meeting.

§ 15-16 May

o The United States-European Union Trade and Technology Council will reportedly meet in France.

§ 16-17 June

o The European Data Protection Supervisor will hold a conference titled “The future of data protection: effective enforcement in the digital world.”

[1] The ACCC therefore recommends that digital platforms establish an industry code to govern the handling of complaints about disinformation. This would relate to news and journalism or content presented as news and journalism, where that content has the potential to cause serious public detriment. This proposal seeks to improve transparency and help consumers by publicising and enforcing the procedures and responses that digital platforms must apply when dealing with these complaints. The proposed code would also consider appropriate responses to complaints about malinformation – information deliberately spread by bad faith actors to inflict harm on a person, social group, organisation or country, particularly where this interferes with democratic processes. While such malinformation has recently become an issue overseas, the ACCC considers it to be a more remote threat than disinformation in the Australian context. If the digital platforms fail to establish an industry code within a designated timeframe, a mandatory standard should be imposed